Patient-led research aims to help others cope with dialysis

It was two years after his kidneys failed that Jeff Costley hit his emotional wall.

He thought he’d adapted pretty well to the changes in his life — dialysis in hospital four times a week, permanent disability leave, new medical expenses, isolation and brain fog from the treatments — but it eventually caught up to him.

“At the start I must have been in denial because I seemed to be doing pretty good,” Costley remembers. “Then I really had a crash moment. I was definitely confused, asking myself, ‘Why is this happening to me?’”

After six months of suffering and searching — and not getting what he needed from a social worker, a psychologist, group therapy and his family doctor — Costley finally connected with a psychiatrist who helped him accept his new normal.

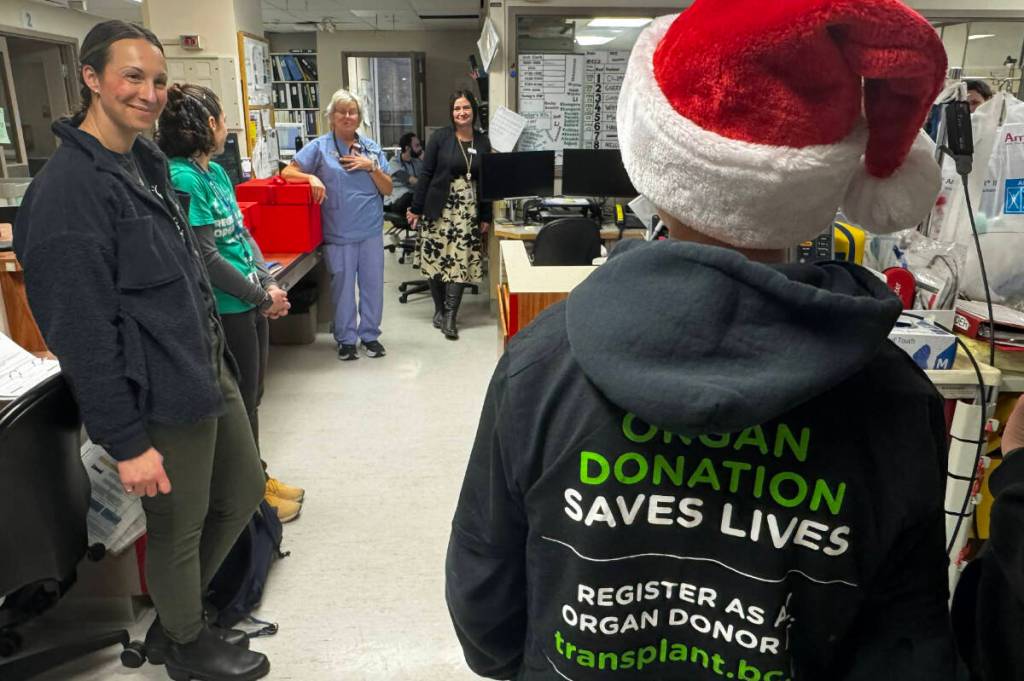

Now, Costley and other Albertans receiving dialysis are working to ensure others don’t have to struggle alone.

Costley is a member of a Community Advisory Committee that recently launched Your Journey: Coping With and Adjusting to Dialysis, an online pathway for mental health care designed by patients, for patients.

Supported by University of Alberta nursing professor Kara Schick-Makaroff, the project aims to bridge the gap between kidney care and mental health support.

“If people receiving dialysis have the agency to broach a taboo topic when they need help, that is a success,” says Schick-Makaroff, co-lead of Mind the Gap, a national research project within the Can-SOLVE CKD Network.

“Success in 15 years would be if people have less burden of depression and anxiety, but I think that’s going to take decades.”

Patient-led change

When your kidneys stop working, dialysis is a life-saving treatment, but it takes a heavy emotional toll. Up to 42 per cent of patients report symptoms of anxiety and 40 per cent have symptoms of depression, putting them at greater risk for emergency visits, longer hospital stays and lower quality of life.

Since it started 11 years ago, the Community Advisory Committee has created a list of mental health resources for patients and is evaluating how well cognitive therapy works for people on dialysis.

Building a new mental health clinical pathway to guide clinicians on how to better support their patients is still a work in progress at the early stages of implementation, but it led to the idea for a patient-focused resource “that everyone can use,” Schick-Makaroff says.

A key aspect of the new guide for patients is the language used. The group intentionally avoided clinical jargon and stigmatizing terms.

“We purposely limited words like anxiety, depression and suicide,” says first author Alexandra Albers, a nurse practitioner graduate student who has worked with the group since 2020. “They felt that words like ‘coping with’ and ‘adjusting to’ dialysis were a lot more inclusive and welcoming.”

Schick-Makaroff notes that Alberta dialysis units have endorsed the inclusion of emotional well-being in their care, but it will take time to break down “silos” between kidney care and mental health care.

“Patients and clinicians have told us this is really important, but it’s new — not just in Alberta and not just in Canada, but around the world,” she says. “We can’t find a single example of where this has existed to date.”

Changing a system and a mindset

Jeff Costley was just 36 when a latent infection took out his kidneys in 2009 and he was put on emergency dialysis. After 16 years and two failed transplants, he now dialyzes at home for nine hours every other night.

He’s set his sights on a bioartificial kidney, which is under development but not yet in human trials. “It always seems like it’s five years away,” he notes.

Costley sees his psychiatrist every six weeks and considers him a friend. His mother moved in with him after his dad died six years ago, and he really appreciates her company and her care.

“Dialysis has really affected my social life,” he says. “I’ve got a lot of food restrictions, so restaurants are kind of a treat. And on dialysis days you’re kind of getting mentally prepared. There’s just a sense of uneasiness that you can’t get over.”

Costley tried going back to university and volunteered for a while as a peer counsellor for the Kidney Foundation, but with the Community Advisory Committee he says he’s found a connection that was missing.

“You’re talking to people who have similar problems and know what it’s like to go through a failed transplant and to have to needle yourself every other day. That’s huge.”

Costley loves contributing to research that improves the health-care system and helps other patients. “We kind of have to change the mindset of what is really required from our health-care professionals,” he sums up.

In the meantime, he advises new patients to speak up.

“Let your nurses and doctor know that you’re having a hard time,” he says. “You need that realization that you can’t do it all on your own. It’s so easy to be hard on yourself, but that is not productive at all.”

This research was supported by Alberta Health Services, the Kidney Foundation of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

link