Screening and diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in children within public healthcare

Patients and study design

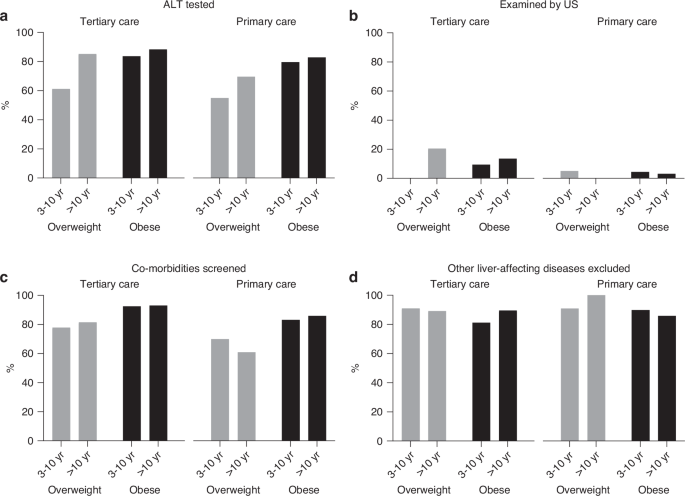

The study was conducted at the Tampere Center for Child, Adolescent, and Maternal Health Research, Tampere University, at Tampere University Hospital (TaUH), and at the Primary Healthcare Unit in the City of Tampere. The study cohort comprised consecutive children aged 3–17 years of age who had received obesity-related ICD-10 diagnostic codes (E65, E66.0-9, and R63.5) at the Primary Care Unit in 2006–2020 or at TaUH in 2002–2020. Their systematically documented medical data at the time of first obesity-related investigations were gathered from the patient records. Possible laboratory investigations, imaging, and other relevant studies conducted within one year of the first associated healthcare visit were also collected. Degree of obesity was verified retrospectively as described below, and individuals proving to be of normal weight were excluded, likewise those with lacking anthropometric data (Fig. S1).

The study design and collection of patients’ register data were approved by the City of Tampere Healthcare Services, TaUH, and the Health Data Permit Authority Findata (permissions THL/246/14.02.00/2021 and THL/2656/14.06.00/2024). According to the national ethical and data processing guidelines, the study required no separate ethics committee approval as there was no intervention, and no subjects were directly contacted. The Declaration of Helsinki principles were strictly followed. Due to strict national data protection regulations, exact results for fewer than five individuals are not disclosed.

Patient data

The following clinical information was collected at the time of the first relevant healthcare visit: demographic and anthropometric data, blood pressure and presence of acanthosis nigricans, prediabetes, lipid metabolic disorders and liver-affecting diseases or medications as recorded by the clinician. Hypertension was defined as systolic or diastolic blood pressure greater than the 95th percentile for age, sex and height22. Possible use of supplements, herbal products, alcohol, or illicit drugs and diagnoses of NAFLD or MASLD and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in first-degree relatives were also recorded.

Anthropometric data included weight, height, body mass index (BMI) Z-score and weight-to-height percentage. Overweight, obesity, or severe obesity were classified based on BMI Z-scores as recommended by the International Obesity Task Force23. Additionally, weight-to-height percentages (WH%) were utilized for children with WH% available, but missing exact weight or height data prevented the calculation of BMI Z-score (n = 73)24. Cutoff values for BMI Z-scores were >1.16 for overweight, >2.11 for obesity, and >2.76 for severe obesity in girls, and >0.78, >1.70, and >2.36 in boys based on national data24. These values correspond to BMI thresholds of >25 kg/m2, >30 kg/m2, and >35 kg/m2 for individuals aged ≥18 years23,24. Equivalent values for WH% were 10–20% for overweight, 20–40% for obesity, and >40% for severe obesity in those <7 years old, and respectively 20–40%, 40–60%, and >60% for older participants24.

The following laboratory values were collected: alanine aminotransferase (ALT), fasting glucose (reference value < 5.6 mmol/l), 2-hour values of oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT, <7.8 mmol/l), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c, <39 mmol/l), high-density lipoprotein (HDL, ≥1.04 mmol/l) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL, <3.36 mmol/l) cholesterol and triglycerides (< 1.13 before and <1.47 mmol/l after the age of 10 years)25,26,27,28. The results of possible relevant imaging studies, including ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), transient elastography, and computed tomography, as well as liver biopsy, were also obtained.

Laboratory exclusion of other liver-affecting diseases included testing for one or more of the following: biliary diseases (γ-glutamyl transferase, alkaline phosphatase, unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin), gastrointestinal diseases (serum immunoglobulin A, tissue transglutaminase 2 antibodies, endomysial antibodies, fecal calprotectin), hepatotropic viruses, inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white blood cell count), kidney diseases (creatinine, urea), liver function tests (international normalized ratio, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, albumin, prealbumin), muscular diseases (creatine kinase), and thyroid diseases (thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyroxine).

Definitions for NAFLD and MASLD

Possible clinical diagnosis of NAFLD/MASLD was recorded. The diagnosis was based on liver biopsy, biochemical markers, and/or imaging, along with the exclusion of other liver-affecting conditions14,15. The updated criteria for MASLD were published in 2023, and were thus applied retrospectively5,6. They included ALT >2x the upper limit of normal (ULN; reference <25 U/L for boys and <22 U/L for girls) or steatosis detected histologically or via imaging, along with the presence of either overweight or obesity5,6. Diagnosis of steatohepatitis and fibrosis was based on liver biopsy. ALT levels exceeding 80 U/L were collected separately due to the previously reported increased risk of advanced MASLD14,15.

Risk factors for MASLD

Prevalence of additional risk factors beyond obesity, as mentioned in the ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN recommendations, was noted, acknowledging that some of the children in the study had been investigated before these were published. At-risk individuals, according to ESPGHAN, included those with increased waist circumference, sleep apnea, presence of acanthosis nigricans, or family history of MASLD, obesity or T2D14. NASPGHAN identifies at-risk individuals as those with increased waist circumference, insulin resistance, pre-diabetes or diabetes, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, and a family history of NAFLD15. All risk factors were defined in accordance with the guidelines. Both recommendations also identified ethnicity, particularly Hispanic origin, as a risk factor14,15. However, this was excluded from the analyses due to a lack of systematic ethnicity data.

According to the NASPGHAN guidelines, all children with obesity and those with overweight and additional risk factors should be screened for MASLD starting at the age of 9–11 years14. Additionally, screening may be conducted on younger children with severe obesity or family history of NAFLD14. We compared the recommendation to the implementation of screening practices, even though this was published after some children had already been screened. Only NASPGHAN guidelines were used for this purpose; ESPGHAN provides no unequivocal recommendations for screening14. The Finnish Current Care Guidelines for obesity, first published in 2005, recommend ALT testing in children with obesity but include no precise screening criteria16.

Statistics

Distributions of continuous variables were assessed for normality by visual examination and, when appropriate, by Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Variables with Gaussian distribution were presented as mean, standard deviation, and range, and skewed variables as median, quartiles, and range. Prevalences of children undergoing examinations or presenting with NAFLD/MASLD were reported as numbers and percentages. Group comparisons were conducted using the Mann-Whitney test for non-Gaussian continuous variables, the t-test for Gaussian continuous variables, and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. When the assumptions for Chi-square test were not met, Fisher’s exact test was used. Changes over time in screening and diagnoses were analyzed by Chi-square test and limited to the years 2006-2020 due to small numbers of participants in earlier years and lack of primary care data. Statistical significance was defined as P value < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

link