Finding a kidney donor in America is a “part-time job” for patients

LANCASTER, Pennsylvania — Jody and her husband Michael have launched a grassroots campaign across central Pennsylvania, with yard signs, bumper stickers, and even billboards, all with one simple message: Kidney Donor Needed.

Kidney care in the United States has improved since President Donald Trump signed an ambitious executive order in 2019 during his first term with the goal of advancing all aspects of kidney disease treatment, from improving access to at-home dialysis to reducing transplant failure rates.

Many of these policy improvements were sparked by Trump’s former Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, whose father lived through dialysis and a kidney transplant. Now, Deputy HHS Secretary Jim O’Neill says he hopes to build on that progress in the second term, citing his experience seeing friends die while on the kidney transplant waitlist.

But even with these policy improvements, the prognosis is not great. The stakes for the Trump administration’s efforts are high.

Two in 10 kidney patients will die within five years of receiving a transplant, and more than half of patients on dialysis will pass away after five years of waiting on the transplant list.

Finding a living kidney donor is the key to avoiding the national average wait time of three to five years on the kidney transplant waitlist. A decent number of kidney disease patients can receive a living organ donation from a relative, and both can live healthy lives with only one kidney.

But Jody is at a disadvantage in finding a living donor because she is one of the 3% of patients on the waitlist with polycystic kidney disease, a rare genetic condition that will eventually put her into kidney failure. Because PKD is a genetic condition, inter-family donation is not always possible.

Jody told the Washington Examiner that she has been on the transplant waiting list since November 2023 and will likely need to start dialysis soon to filter her blood. The national average is three to five years on the kidney transplant waitlist.

Jody described her experience as “a true roller coaster” of emotions, but her goal is to stay positive, “because if not, I think you will fall off the cliff a lot faster.”

The waitlist for a kidney

Jody is among roughly 103,000 on the national transplant waitlist, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration, as of September 2024.

The overwhelming majority on the list, 87%, are waiting for a kidney. Another 2,100 are waiting for a kidney and pancreas system transplant to treat the joint conditions of genetic Type 1 diabetes and kidney failure.

According to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, a public-private partnership that manages U.S. organ donation and is overseen by HRSA, there were 28,378 kidney transplants in 2025.

That’s a 52% increase over the past decade, with only 18,597 kidney transplants in 2015. The number has nearly doubled since 2000, when fewer than 15,000 kidney transplants were performed in the U.S.

Trump’s first-term executive action spurred a great deal of this increase by streamlining the transplant process. Regulations that followed the executive order required organ procurement organizations that coordinate transplants to expedite their kidney matching processes and reduce the number of organs discarded after retrieval from deceased patients.

The first Trump administration also boosted financial incentives for living donors by increasing the income limits for eligibility to receive federal compensation for expenses associated with donating, including travel and child care.

People only need one functioning kidney to live a healthy life, and the surgical recovery time is often less than two weeks. HRSA reported that, of the nearly 46,700 total organ transplants in 2023, just under 7,000 were from living donors.

Although donation and transplant rates have increased, the number of patients on dialysis has grown at a faster rate, meaning that demand for kidneys continues to outpace supply.

Only four in 100 patients on dialysis received a donor kidney in 2024. On average, 13 people in the U.S. die each day waiting for an organ transplant.

Marketing for a kidney donor

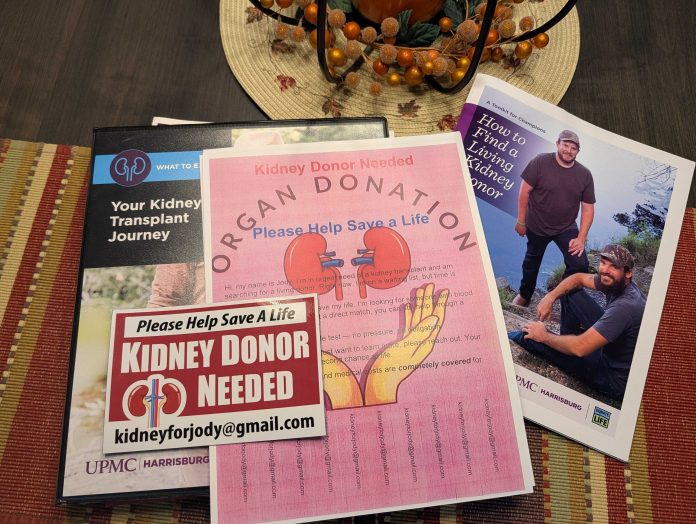

Michael, Jody’s husband, has been using his background in sales to wage what he calls a “guerrilla marketing campaign” to find a living donor and get his wife a kidney since last April.

Finding a living donor is crucial to avoiding a lengthy stay on the transplant list. It’s also an essential step if the patient is hoping to get a transplant before needing to start dialysis, which improves the odds of a successful transplant.

In addition to bumper stickers and yard signs, Michael has an advertisement in several local Catholic Church bulletins and has posted flyers locally with the email address [email protected]. He was able to claim a handful of billboards between Harrisburg and Philadelphia for free as a generous donation to Jody’s cause.

The couple said the campaign to find a donor is effectively a part-time job on top of the time and energy spent on medical care.

“We don’t want to be known as those people that are constantly asking, you know, for someone to get tested or whatever, but at the same time, you know, it’s our part-time job,” Michael said.

Michael also plans to go to sporting events in the region with a T-shirt and sign highlighting the kidney campaign in the hopes of getting noticed, a strategy that Jody’s doctors said has worked to attract living donors for their prior patients.

It is standard practice for transplant medical teams to coach their patients on which strategies former patients have used to get connected with a living donor. Jody’s medical team through the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center branch in Harrisburg even gave the couple pamphlet materials on marketing tactics to find a living donor.

“If we had to do it over again, we probably would have started right when the filtration rate dropped below 20%, just because it takes an inordinate amount of time to, you know, basically put the ground game together in order to do the advertising,” Michael said.

Normal kidney function is a filtration level of 90% or more. A filtration level at or below 20% is the standard for getting on the transplant waitlist, and a level less than 15% is diagnosable kidney failure.

Jody said her goal is to stay positive “because if not, I think you will fall off the cliff a lot faster.”

Personal experience drives policy improvement

The experience of top officials with kidney disease has helped the past decade’s policy changes in kidney transplant care.

Azar, who was central to advancing Trump’s 2019 kidney executive order, told the Washington Examiner that his father’s experience with the transplant system was central to his advocacy of improving federal financial support for living donors to address organ scarcity.

The former HHS Secretary said that his father was lucky to have received a kidney from the owner of a local restaurant that his father frequented. Azar’s father passed away in April 2020, but he was able to enjoy a longer life thanks to his organ donor.

“I got to see the challenges of dealing with the transplantation system, of the wait, and if it had not been for the generosity of this individual, one doesn’t know if he ever would have made it through the transparent list process,” Azar said.

Paul Conway, a kidney transplant recipient and policy director of the American Association of Kidney Patients, told the Washington Examiner that Azar and other policy advisers in the first Trump White House who worked on the executive order were “willing to throw down high marks, high goals” because of their intimate experience with kidney patients.

“Secretary Azar not only walked the walk and talked the talk, but he got it on an empathetic level. He understood the human impacts of organ failure,” Conway said.

The order and subsequent policy “shook up” the healthcare industry that had become accustomed to “accepting high cost, high mortality kidney care,” Conway said.

In the second Trump administration, Deputy HHS Secretary O’Neill has taken on a similar role, also having a personal, patient-centric view of the transplant system.

O’Neill has had a long history of working on organ donation policy, coming under fire before his Senate confirmation for past statements in support of opening a commercial market for organs to address the scarcity problem.

In September, O’Neill announced an additional $25 million would be given this year to the Living Donor Program to incentivize donations as well as fund research models to better support living kidney donation. The administration is also heavily investing in xenotransplantation, or using genetically modified pig kidneys, as well as other pioneering biotechnology options.

O’Neill said during the speech that the Trump administration’s ultimate goal is to modernize the organ donation system and “bring us into a future in which waiting for a transplant will become a bizarre relic of the past.”

The waiting is the hardest part

In the meantime, Jody said, one of the most frustrating parts as a patient is, after working hard to find a possible donor, not having any follow-up as to whether it will result in the transplant as hoped.

After a patient finds another person willing to undergo the screening process for potential donation, the medical team is not allowed to tell the patient anything about the results of the testing unless it is a successful match and the transplant moves forward.

“It’s like getting a fish on a line and you’re reeling it in, and then it lets go, but you don’t know it let go,” Jody said. “You keep reeling, thinking that something’s on the line and nothing’s on the line anymore.”

The couple has found several people potentially willing to donate and connected them with their medical team. Some have directly informed Jody that they were denied by the medical team for one reason or another, but others just go silent.

“I believe the common vernacular they use now is ‘ghosting,’” Michael said.

‘TRANSPLANT TOURISM’ SPARKS HOUSE INVESTIGATION

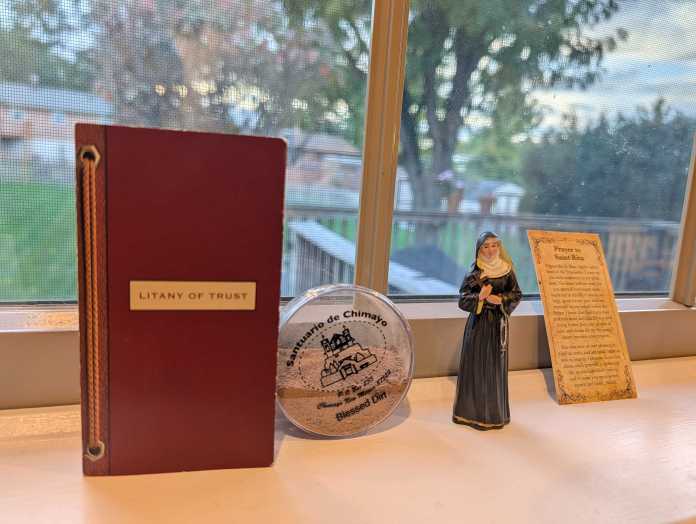

Jody and Michael, both practicing Catholics, say the experience has strengthened their faith. They have a statue of Saint Rita, patroness of impossible causes, on the windowsill above their kitchen sink.

“I try not to think about it as much,” Jody said. “I want to live my life as Jody, not PKD Jody. I don’t want people to feel sorry for me.”

link